Noir

Poster Hunt #11 - Nightfall (and New Blog! New Blog!)

First up, here’s a Poster Hunt for July.

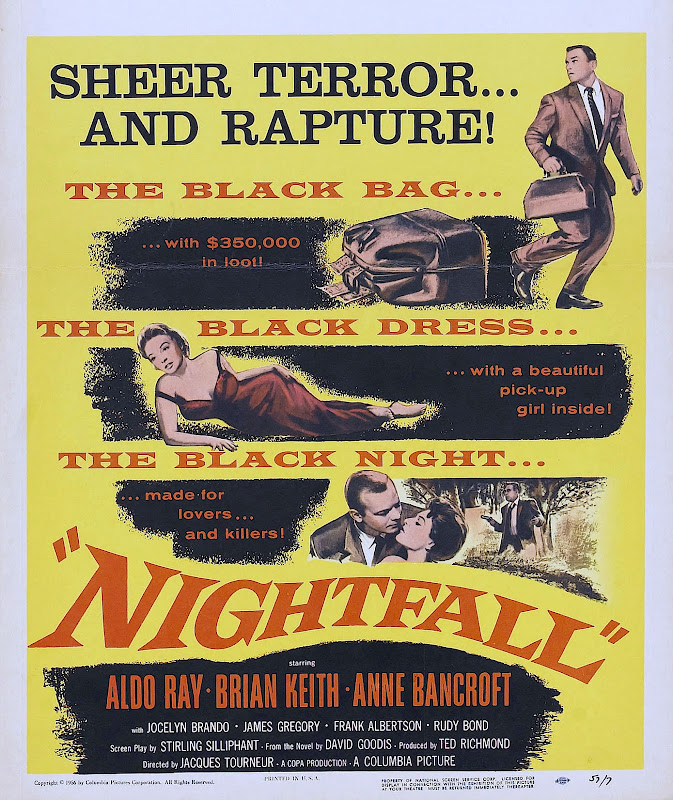

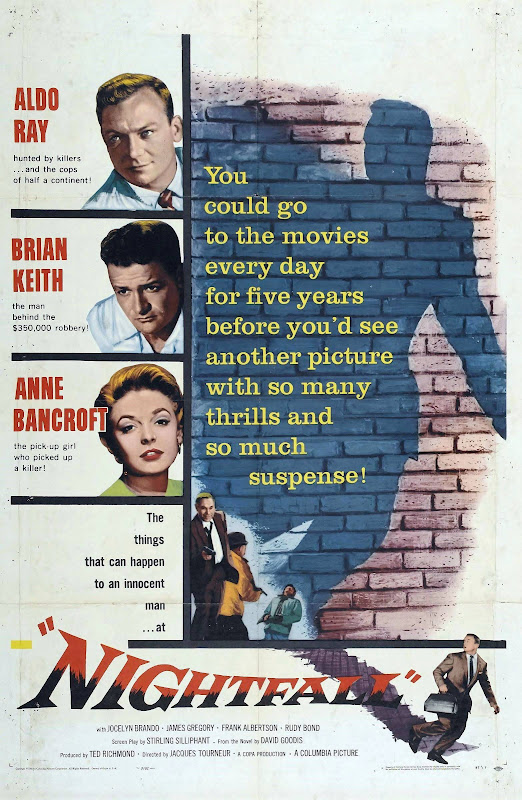

Here are a couple of posters for Jaques Tourneur’s Nightfall (IMDb) from 1957, starring Aldo Ray, Brian Keith and Anne Bancroft. I don’t write much about the films for these Poster Hunt posts (as I select them for artwork rather than the film - most of them I haven’t seen), so if you do want to know more about the film I’ll direct you to this comprehensive blog post at Noir of the Week.

Every day for five years? That’s quite a claim!

*************************

Secondly, I’d like to introduce you to Chopping Mall’s edit: SHORT-LIVED, NOW DEFUNCT) new sister blog, Cult Collage. The focus of this one will be mostly pictures (although music might feature occasionally too) and it’ll pick up on interesting film and non-film related ephemera. It’s pretty difficult to describe what I intend it to be; I think a collection of interesting images sums it up best, with a leaning towards pulp-art.

Currently it only has the 11 Poster Hunt pages from this blog but it’ll be updated often (far more often than this one) with other interesting posters, leaflets and ephemera.

So head over to:

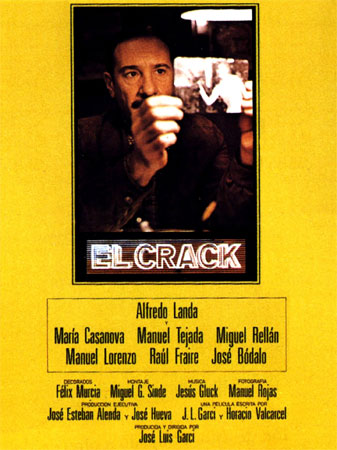

El Crack

When you think of film noir, you think of it’s true home - America. We think of corrupt cops, mean streets, whisky on the breath of hard-working loner detectives and screeching tyres through the city.

As you turn towards the 70s, the real Noir has long ceased to be and is now replaced by the neo-noir. The relationship between these films and the original classic Hollywood output is confusing and often contradictory. They are at once parodies of classic noir, re-imaginings of the genre and cinematic love-letters to a genre left behind.

This brings all sorts of other concerns; unless they go to the extent of setting themselves within the time period of the classic noir, contemporary issues become involved, the world had changed between the 40s and 70s and so the hard-boiled detective story had to as well. Similarly, if we move the narrative away from America, the different geography brings it’s own tensions, styles and attitudes. The final product is, in many respects, a million miles away from the film noir, yet somehow remains linked.

In real terms, films like El Crack (Spain, 1981) are as far removed from true noir as American teen slashers of the 90s are from Italian giallo thrillers. Only a few core elements are left to connect the two genres yet somehow you can’t help but see a link.

In making El Crack, they certainly intended the link to be visible; from the opening dedication to Dashiell Hammett to the corruption, gunshots and nighttime city, this is both desperately seeking comparisons to American noir and making a statement of Spanish independence. It is both derivative and original. It’s also pretty good fun.

Alfredo Landa plays the central detective, Germán, excellently. It is his performance that both links and distances this from the American noir. He is an ex-cop, a workaholic detective who is too honest and honourable for his own good. He passionately works late into the night on his case - a missing girl - fuelled by coffee, cigarettes and (asserting the Spanish-ness) the odd calamari sandwhich.

The other characters are mostly ‘by-numbers’ hard-boiled characters; Germán has a slimy ex-thief assistant and lives in a world populated by crooked cops and businessmen who think themselves above the law. Where it branches far from Noir however, is Germán’s love interest. I don’t know whether it came about as a result of Spanish Catholiscism, a deep-routed belief in the family unit or whatever else but, rather than the femme-fatal of the American noir, charged with sex and danger, Germán is pursuing a relationship with a pretty but conservative nurse. It’s all very civilised; he picks up her daughter from school while she works, they go for strolls in the woods or off to see a film. It’s all very… nice.

These niceties only serve to make the brutality of the last third of the film more brutal. Germán may be a much milder man than the creations of Chandler or Hammett, but when he’s pushed he acts surprisingly coldly in pursuit of justice.

The only real criticism of the film is that the pacing is a bit awkward. European films do tend to be a lot slower than American films; we seem to prefer slow build rather than a rollercoaster of climactic moments, but this one is decidedly on the slow side of ‘slow-build’. The first half and hour to forty minutes do drag somewhat but, I promise you, it’s worth persevering as the film builds slowly but surely towards a thrilling ending.

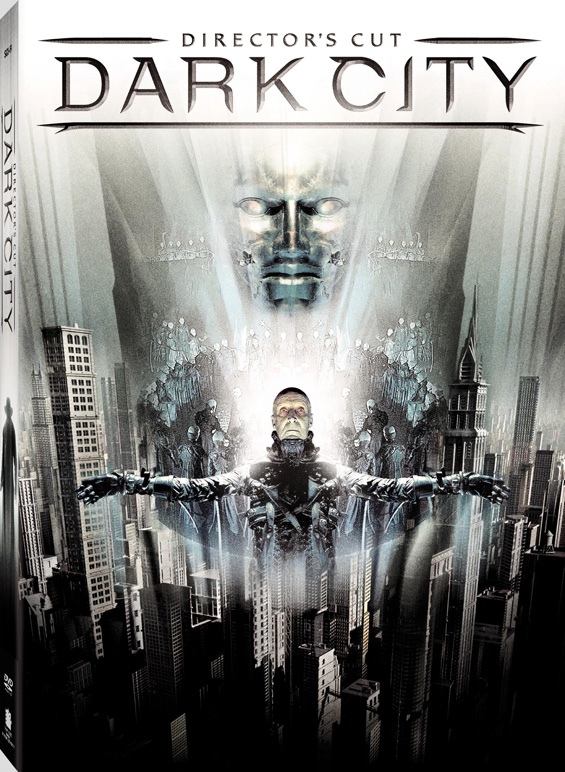

Dark City

[I don’t know if the version I saw was the director’s cut…]

In my recent post on The Black Windmill, I mentioned that I watched a number of films that I would define as the criminally ignored. Well, if there is any film that earns the title “Criminally Ignored”, it must surely be Dark City.

Dark City is a beautiful film, Dark City is an interesting film, Dark City is a good, but most of all, Dark City is an underrated film.

It’s not hard to see how and why it was elbowed so cruelly from the limelight that it so clearly deserved; Dark City was filmed at almost exactly the same time as the Matrix, it was filmed using many of the same sets as the Matrix, it shared many of the same concerns as the Matrix. In fact, watching it after having seen the Matrix, you might easily think that they’d lifted large quantities from the Matrix.

Both films show us a world in which the naive citizens are unaware of the scheme which they are a part of, a world which strange characters with a collective consciousness control, alter and move through as they please, a world where one somewhat unwilling hero represents the hope for humanity by escaping from the confines of his artificial-reality prison. Yes, the two films are really that similar.

There are, despite this, many diferences too. Part of the central thrill of the Matrix (and no-doubt a key factor in it’s success) is how intune it was with technology and our paranoia about computers and computer control. Whilst the Matrix is a virtual reality prison, Dark City relies on much more traditional (and so prosaic) fears. Here, rather than robot ‘agents’, the fake city is manipulated by aliens who are studying humans, each night they alter the city, fiddling with individual memories and observing our reactions. They turn rich into poor, poor into rich, invent backstories of happy summers and tragic memories. If anything, this is more threatening than the Matrix; our lives are not simply faked from day one, but altered every night without our knowing. Every single memory you have may well be artficial.

So why wasn’t it as successful as the Matrix? Visually, though very different, it is absolutely on par, for all the leather-clad cool of the Wachowski Bros. offering, here we have a city of film noir beauty, all night-time streets, phosphorescant street-lamps and chain-smoking detectives. So what WAS the crucial deciding factor? (For the purposes of artistic interest we are ignoring anything as dull as advertising budgets etc)

The answer, to my mind at least, is that there is very little between the films in terms of real merit, but only in terms of their awareness of the interests of the age (or the zeitgeist if you will…). The Matrix tapped perfectly into our interest at the time of release; where technology was on a balancing point between the realm of the hacker uber-nerd (Neo) and a means of control. Much as the zombie movies of the 70s mirrored Cold-War nuke paranoir, the Matrix excited us because it was able to tap into our fears at time. By comparison, however good a film Dark City may be (and it IS a good film) its aliens, its detectives and its film-noir atmosphere were far less striking.

Oh yeah, all that and the fact that it gets pretty silly towards the end…

Definitely worth a watch though.

Trailer follows: